The Story of the Montour Log Raft

By Van Wagner and Karl Shellenberger

Photography by Cory Poticher

except where noted

Log Rafting on the North Branch of the Susquehanna River:

The Story of the Montour Log Raft

The Story of the Montour Log Raft

By Van Wagner and Karl Shellenberger

Photography by Cory Poticher

except where noted

Log Rafting on the North Branch of the Susquehanna River:

The Story of the Montour Log Raft

In the summer of 2003, a group of Pennsylvanians discussed the idea of building a 19th century log raft and floating it on the North Branch of the Susquehanna River. About one year later, a raft over 100 feet in length left from a point near the border of Columbia and Montour Counties and headed downstream towards Sunbury.

The project of creating the Montour log raft was two-fold. First, it

helps to tell the tale of men long since passed who made their living from

the White Pine forests of Pennsylvania by floating the timber to the markets

in the southern parts of the state. Second, it is the story of dozens of

people from the 21st century who, in the process of discovering

history, gained a deeper appreciation of heritage, community, and self.

Photo from Lycoming County Historical Society Museum

Although the logging industry of Pennsylvania was centered around Williamsport and the West Branch of the Susquehanna River, the North Branch also contributed a great deal to the story of Pennsylvania timber. The virgin forests of Penn’s Woods held some of the finest White Pine ever seen. This species of tree was invaluable to American settlers. The grain of this tree is straight and true, and it will resist rot and will not warp. Although very light in weight, it is remarkably strong. Not only was this resource valued by the naval vessels for masts and spars on ships, but the farmers in Pennsylvania’s southern tier had an insatiable thirst for wood to construct homes and barns. White Pine floats very well and was also used to transport goods from the frontier to markets as far away as Baltimore.

There's a misconception that all virgin timber consisted of large diameter

trees. Loads of virgin timber would come off the mountains on its way to

the anthracite or hard coal region of Pennsylvania where it would be used

for mine props and posts. The coal industry in the Scranton and Wilkes-Barre

area owned large blocks of land in the seven mountains and owned it primarily

to obtain the wood for mine props. (Jim Nelson, former State Forester for

DCNR).

The Rafts

There were four kinds of rafts. The first was a "spar raft" which was made by lashing tall straight tree trunks together. Other raft types included: a "timber raft" which was made of squared logs, a "lumber raft" which consisted of logs that had already been sawed into lumber, and lastly "arks" which had a flat bottom and was constructed in a manner to allow for carrying cargo such as coal, grain, or other goods from the interior. ("The Long Crooked River")

On several occasions, local iron mills in Danville were forced to use ark rafts to transport their iron T rails and other products due to work stoppages and repair work on the canals and railroads. (Sis Hause)

By 1796, rafts from both the North and West branches of the Susquehanna were making the trip downstream, some traveling as far as Norfolk, VA. (S. Stranahan) The industry quickly escalated over the next decades until the river became a super-highway of rafts. Between the 18th and 23rd of May in 1833, 2,688 arks and 3,480 rafts floated past Danville. That averages out to over 1000 rafts and arks per day or between 1 and 2 rafts every minute of the day. Their cargo was mostly grain and lumber. (Intelligencer 6/14/1833)

Photo from Lycoming County Historical Society Museum

The last actual raft that came down the Susquehanna River (unknown whether

North or West branch) came down in 1917, and was sold to a mill in Marietta.

(Jim Nelson, former State Forester for DCNR).

The Raftsmen

"Now a Susquehanna waterman…will go on board an ark or a raft somewhere about the New York line, in March, April, and May, descend to the tide water of the Chesapeake, and then return home on foot, through mire, rain, and all sorts of weather, at the rate of 50 or 60 miles a day. When he gets home he jumps upon another ark or raft, and enacts the same feat over again – making five or six trips during the season of high water. " (unnamed observer of 1800’s log rafts)

Later, loggers headed into the headwaters of the Susquehanna for the Eastern Hemlock tree. The bark was used to make tannic acid for Pennsylvania’s thriving tanneries, and the wood was found to be a very suitable lumber.

Most of the logging that was being done during the late 1800s to early 1900s was done by northern European loggers, immigrants that came from Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Poland and some of the Slovak countries. They would build a shanty and live in it until the timber was totally cut and then move on to the next job. (Jim Nelson, former State Forester for DCNR)

A voyage across the Atlantic does not involve so much danger to life and property, as the navigation on the river. This was reaffirmed in March 1938. A group of former lumbermen built a commemorative raft with the intent to navigate it from the small West Branch town of Burnside to Harrisburg. They named the endeavor the "Last Raft." On the morning of March 20, the raft tied loose from its overnight stay in Williamsport. Later in the day, tragedy struck. The raft, with 48 people aboard, slammed into two bridges between Muncy and Montgomery. Seven people were drowned as the raft tilted and dumped many aboard. The raft did continue towards its destination and was eventually tied off about 8 miles above Harrisburg and the timber sold to a lumber buyer.

Other attempts to construct and float a log raft have occurred since the "Last Raft," although none on the North Branch. These other rafts include one built by Lycoming College students in 1964, a raft on the West Branch in 1976, and another raft on the West Branch in March of 2004 to commemorate the bicentennial of Clearfield.

Sources

Sis Hause, Danville Historian. Danville, PA

S. Stranahan. "Susquehanna River of Dreams" John Hopkins University Press, 1993.

The Danville Intelligencer Newspaper, Danville PA 6/14/1833

MYERS, Richmond E "THE LONG CROOKED RIVER". (The Susquehanna) Boston,

(1949) The Christopher Publishing House

Jim Nelson, former State Forester for DCNR (Pennsylvania)

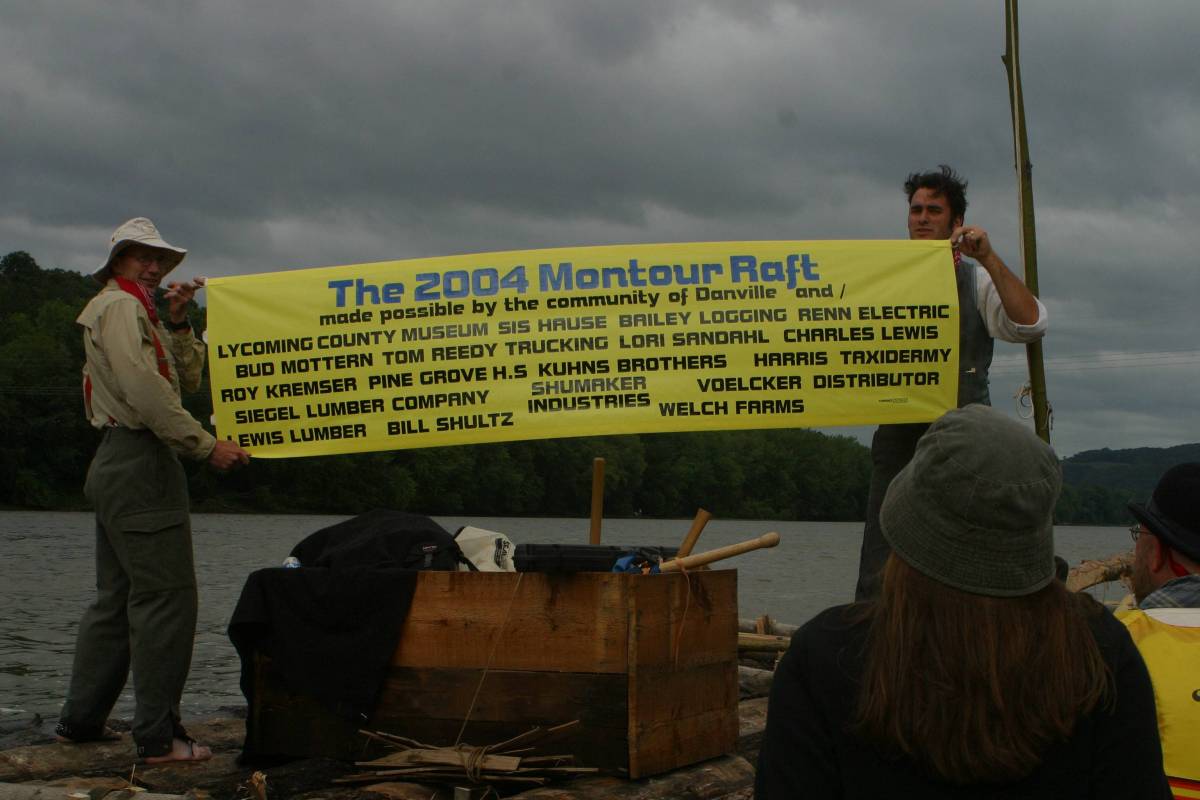

Construction of the Montour Log Raft

July 2003

Karl Shellenberger and Van Wagner start very preliminary discussions on what it would take to build a log raft and to float it on the Susquehanna River.

November 2003

Logging begins with Bill and Si Bailey on the land of Lori Sandahl in Elysburg Pa (Northumberland County). About 1500 Board feet of White Pine are logged from this land using a team of horses to skid each log to the landing.

April 2004

An additional 2000 board feet of White Pine logs are donated by Kuhns Brothers Lumber, Union County Pa. Construction drawings explaining raft design of the Last Raft of 1937 were located with help from the staff Lycoming County Historical Society Museum. The drawing is from the book titled "The Last Raft" by Joseph Dudley Tonkin (1940).

May 2004

The logs are all decked on the property of Bill Shultz on the North

bank of the River near the border of Montour and Columbia Counties. Construction

began under the direction of Ken Kremser and Van Wagner. Logs were inventoried

and measured so that a crude blueprint could be created to plan for the

location of each log. In total there were 28 logs ranging from 20 – 26

feet in length.

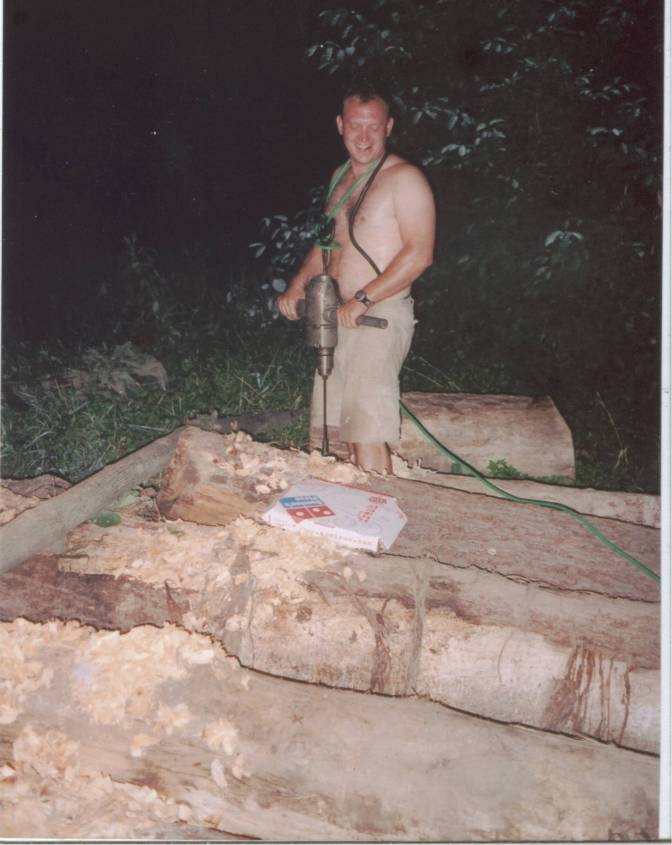

June 2004

Each log was skidded into place on land as it would appear in the water as part of the raft. This was not done in the 1800s. We chose to do this to allow for easier planning ahead of time. As shown in the blueprints, the raft consisted of 3 sections end to end. Each section was about 9 logs wide. Each "length" of raft (3 logs end to end) would contain 2 logs 26 feet in length and one log 20 feet in length. The position of the shorter log would vary in each "length" to allow for overlapping in the joints.

The sections of the raft would then fit together end to end like a puzzle, rather than meeting at a flat seam. Once the logs were all in place, we cut hickory trees to serve as lash poles across the top of the raft. A total of 8 lash poles were needed, one at each end of the raft and three at each of the two joints on the raft. The hickory poles were no more than 15 feet long with a diameter ranging from 4-6 inches.

Once the lash poles were laid in place atop the raft, we began drilling holes two inches in diameter, and 8-10 inches deep. One hole was needed on each side of the lash pole. The logs at the front and back of the raft were given 4 holes total for extra strength. All told, this raft had 154 holes. Ken Kremser drilled 153 of them; Van Wagner drilled one single hole.

While the holes were being drilled, a team of workers were busy making the "bows" out of green White Oak. The Oak was logged on the land of Steve Welsh. We cut first and asked permission later. Green wood was needed to allow for bending of the thin strips of wood. The bows were about 25 inches long, 1 ½ inches wide, and about 3/16 inches thick. They were cut from the rounds of White Oak using a tool called a fro. It was important to stay true with the grain as they cut each bow to avoid varying thickness.

The bows would be bent into a "U" shape and once construction began, inserted in each hole on either side of the lash poles. Ash pins would then be driven into each hole to hold the bows in tight. The pins were about 1 ½ inches square by 12 inches long. They were made by students at the Pine Grove Area High School out of lumber donated by Siegel Lumber Company, Pine Grove.

The raft needed 2 tillers and tiller mounts. The tiller mounts were

cut out of one solid piece of Spruce. Historically hardwood such as Oak

was preferred. The tiller mounts were about 55 inches long, 24 inches wide,

and 16 inches tall. A hole was drilled into the top of the tiller mount

and an Oak axle was inserted. Holes were drilled, 2 inches wide, completely

through the ends of the tiller mount and several inches into the white

pine logs under the mount. Later, wooden pegs were pounded down through

the tiller mount and into the logs below to secure it on the raft.

The two tillers were made from Red Pine logged on the land of Charles

Lewis. White Pine "blades" were then sawed by Bud Modern. The blades were

about 10 feet long, 2 feet wide, and 2 inches thick. A slot 4 feet long

and 2 inches wide was cut into the fat end of the tiller. The blade was

then inserted into the slot. The combination of the blade and tiller is

called the sweep. Once the correct angle was achieved between the blade

and the tiller, holes were drilled and then pegged to lock the blade in

place on the tiller. Then the center balance point was found by balancing

the completed sweep on the tiller mount. An oval hole was then created

through the tiller. The sweep was then lifted, and lowered onto the axle

on the tiller mount. The sweeps should be angled in a way so that the blade

is in the water while the sweep handle is about chest high for the oarsman,

and out of the water when at the knees of the oarsman.

July 2004

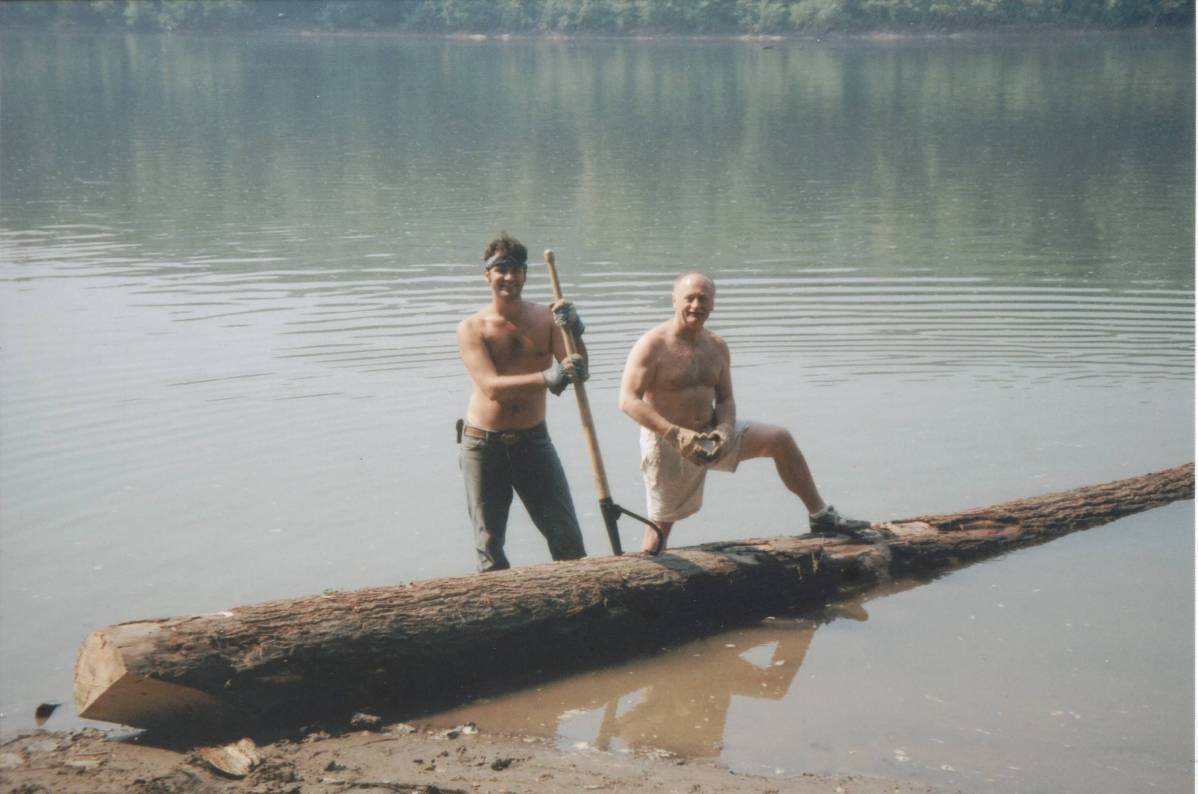

It was now time to begin putting the raft together, which had to be done in the water. First, a long Hickory lash pole was extended into the water at a 90 degree angle from the shore. The butt of the pole was attached to a tree on shore and a rope was tied to the other end of the pole and attached to the shore upstream at a 45 degree angle. This pole was the frame onto which the raft would be built.

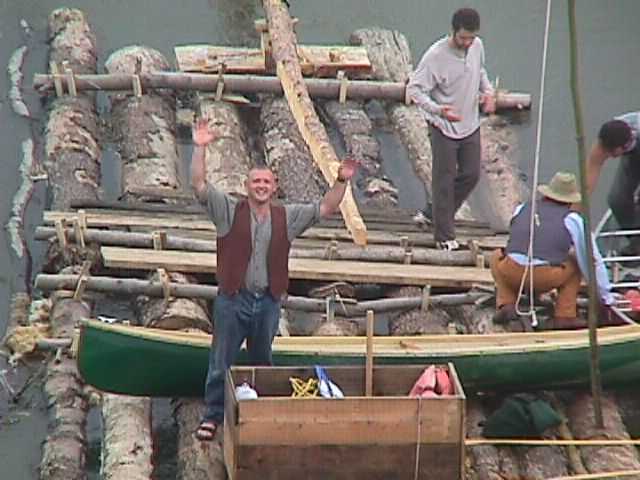

The White Pine logs were pushed into the river using a tractor, one at a time. A crew of people in the river would walk the logs into place and attach them to the lash pole using the bows and pins. Once the first section was complete, the second lash pole was placed atop the raft and the process continued until all three sections were complete. The total length of the raft at this point was 70 feet. Once the tiller mounts and sweeps were in place the raft measured 105 feet end to end and was about 15 feet wide.

Holes were drilled all the way through 2 logs in the rear of the raft. Steel bars (1 ½ inches thick) were placed into the holes all the way to the river bottom. These served as our brakes. Rafts in the 1800s sometimes used saplings in a similar manner.

A tool and cargo box was added on the deck built from lumber salvaged out of the old Coles Hardware warehouse on Mulberry Street in Danville. Robb Baylor, present owner, was renovating the property and donated the lumber, probably over 150 years old, to the cause. Ironically, some of the lumber used in making this box may have very well come to Danville as part of a log raft in the 1800s. This box was the only place where nails were used on the entire raft. The raft was held together using nothing but wood.

A replica of an 1861 U.S. flag was hand-sewn by Sherri Oberdorf and raised on the raft.

People who worked during the construction phases of the raft: Ken Kremser,

Aaron Myers, Mark Lewis, Van Wagner, Sonia Crane, Brian Crane, Sherri Oberdorf,

Todd Oberdorf, Jack Curry, Francy Moyer, Tamara Wagner, Dan Sellers, Dan

Gable, Chris Johns, Cleo Weader, Mark Weader, David Weader, Bill Hause,

Gary Gilmore, Josh Poticher, Cory Poticher, Steve Richard.

THE VOYAGE OF THE MONTOUR

July 15th

The crew of the raft was as follows:

Ken Kremser, Steersman (manned the rear sweep)

Aaron Myers, Oarsman (manned rear sweep)

Van Wagner, Pilot (manned front sweep)

Mark Lewis, Oarsman (manned front sweep)

Karl Shellenberger, Oarsman (manned front sweep)

Rich Pawling, River Hog (assisted where needed)

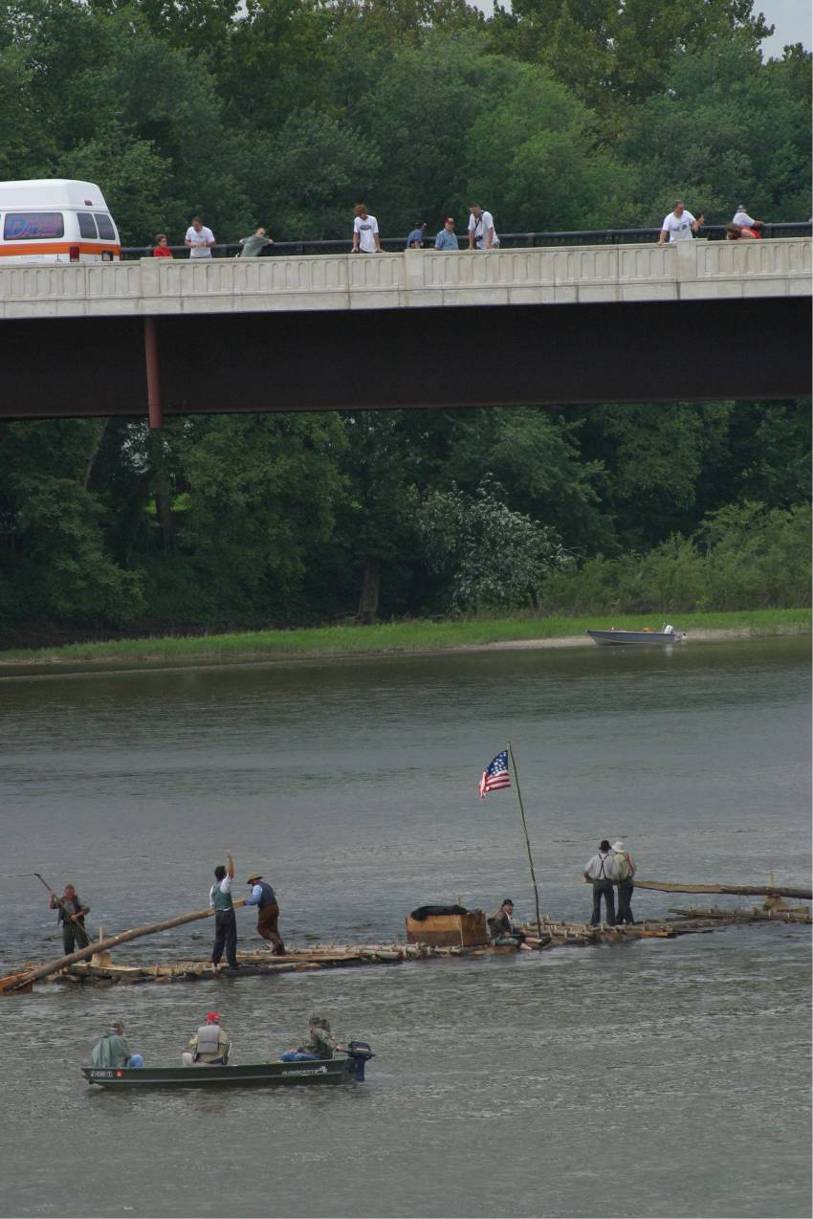

After a breakfast at Pappas Restaurant in Danville, the crew hit the raft. By 8:45 the flag was raised, and a can of Piels "Draft Style" beer was smashed on board to officially christen the raft as "The Montour." The crew then tied loose and headed downstream.

One final test of the tillers and the brakes were removed and the rope to shore was untied.

By 9:15 am, the crew was headed to the North side of Snyders Island. There were several known shallows on the side of the island but the crew made it passed without a hitch.

From Snyders Island on to

Danville, crowds of people lined the riverbank, cheering on the raft as

it passed. Close to 100 people gathered at the boat launch by the Danville

State Hospital.

From Snyders Island on to

Danville, crowds of people lined the riverbank, cheering on the raft as

it passed. Close to 100 people gathered at the boat launch by the Danville

State Hospital.

Van’s only Parodi cigar was a bit soggy after a unexpected dip in the

river.

The crew was joined by Rich "The River Hog" Pawling who helped with the cause.

A flintlock rifle was kept handy to ward off Susquehanna River pirates,

also to keep the crew "motivated".

First pregnant lady on the Montour log raft!

Briefly stuck on the rocks as the crew neared Danville.

There was a steady upstream breeze which slowed the raft slightly. It

was about 12:30pm when the group reached Danville. There was a slight scare

when the raft became stuck on a rock just upstream of the old Danville-Riverside

bridge. Shallows were hard to see due to the ripples on the water caused

by the strong wind. Once the crew realized they were stuck, they sprung

into action. The six men on board took the two steel brakes and carried

them into the water behind the raft. With a few good pushes, the raft was

pried off the rock and on its way again.

At about 1pm, the raft passed below the bridge between the second and

third bridge piers (the first pier being the one closest to Danville).

July 18, 2004

After spending the weekend in Danville during the Iron Heritage Festival,

the raft is once again tied loose and is floated downstream a few miles

to a location in Point Township, Northumberland County.

July 22, 2004

Raft is tied loose again and floated downstream to near the border of

Upper Augusta Township and Rush Township, Northumberland County.

July 28, 2004

Raft gets hit by a floating log during a period of high water and takes

off downstream. A group of firefighters and Ken Kremser were able to rescue

the raft and float it downstream to Packers Island in Sunbury, where the

raft ended its journey.

Photo by unknown photographer

Photo by unknown photographer

August 2004

The crew organized on Packers Island in Sunbury and began dismantling

the raft. A crane was donated by Shumaker Industries for hoisting the logs

out of the river. The last log was removed from the water on August 8th.

Each bow was cut so that

the log was now free from the lash pole.

Each bow was cut so that

the log was now free from the lash pole.

Logs were then pushed free one at a time.

Chains were then attached to the logs and they were hoisted out of the river for the first time a month.

Each of the tillers was hoisted using the crane and saved for future display.

Marc showing off his log rolling skills that he learned while at PSU Mount Alto.

Down to only a few logs and a tiller.

Ken Kremser operated the crane all day braving levels of carbon monoxide that would kill most mammals and some birds. After several hours his reaction time on the chain controls became a little off. He earned the name "Crazy Chains Kremser".

Josh Poticher, Van Wagner, Ken Kremser, Aaron Myers, Marc Lewis.

Ready to be loaded on the log truck and shipped to a saw mill.

September 2004

Mike Robbins sawed the logs into over 5000 board feet of lumber. Mike

used his portable band saw to mill all 30 logs into 3 stacks of boards

that were each over 5 feet tall each. The lumber will be used to build

benches in cooperation with the Montour County Recreation Authority for

the F.Q. Hartman athletic complex. Another portion of the lumber is being

donated to the Danville Area High School FFA program to be used by the

agricultural science classes.

RAFT STATISTICS

Length - 105 feet (including tiller blades), about 70 feet not counting the tillers

Width - Varied, averaged about 15 feet

Estimated Weight - 20-25 tons

Total Lumber Contained in Raft - about 5000 board feet

Total Days of Travel - 4

Total Distance of Travel - about 15 miles

CONTACT INFORMATION

For more information about the Montour Log Raft, please contact:

Van Wagner

900 Avenue F

Danville, PA 17821

or

Van Wagner: (click here for contact info)

Karl Shellenberger: karlshell@yahoo.com